Investigative Stories

On January 6, 2023, Bhawana Shrestha bought 5 ropanis of hillside land at Siddhara-3 in Arghakhanchi district. That Bhawana, a local resident of Kavre, had bought land that was not suitable for cultivation of crops defied logic. But she was not alone. That same month, Bibek Shrestha, a local of Kathmandu, also bought several strips of land, with a cumulative area of 62 ropanis, in Siddhara.

On April 4, 2023, a company, Prakriti Holding and Agro Private Limited, was registered stating it was located at Kathmandu Metropolis-30. Two months later, the company bought 15.5 ropanis of land in Thada, Arghakhanchi.

A secondary teacher at a school in Shitganga Municipality, Arghakhanchi says that over the past two years, the trees at Khoriya lands registered as private properties in the district’s Jukena, Thada and Siddhara village have been emptied out.

“Those who have come from Kathmandu and those who have migrated from here to Tarai have not left any Khoriya land alone,” the teacher says. “The land that was initially being bought at Rs 5-7 thousand per ropani is currently being traded at Rs 30-40 thousand.”

According to another local resident, Khoriya lands at those villages are being traded at speed currently. Various individuals have purchased as much as 1,000 ropani land in Siddhara alone on the pretext that they would run agro farms there. The trend is the same at Jukena and Thada villages.

According to the teacher, the purchasers have formed a group of local helpers who monitor the land, calcuate the numbers of Sal trees at Khoriya lands and thus begin the trading process.

Officials from Survey and forest offices have been measuring the lands. “The villages are emptying out with rapid outmigration and the lands are left barren,” the teacher says. “And instead of leaving the lands behind, they are opting to sell them. There’s hardly any land with Sal trees that remains unsold.”

Over the past two years, the trend of the sale of private land is on the rise from Karnali Province’s headquarter Surkhet to Udayapur’s Chure region. The trend is especially more pervasie in Syangja, Pyuthan, Arghakhanchi and Palpa.

Jibnath Paudel, chair of land registration office in Waling, Syangja, says that the trade of barren land in the area—especially around Biruwa, Archale, and Arukharka villages—has been on the rise over the past two years. “Locals say they have sold it upon getting the right value for their land,” Paudel says.

Gyan Bahadur Sinjali, chair of land registration office in Rampur, Palpa, says that the number of people taking permits to fell trees has been on the rise over the past 2-3 years. After the survey office confirms the land area, the forest office permits the felling of trees, according to Sinjali. “The number of those seeking permits to do so has been on the rise in recent months,” he says.

Purchase of Khoriya land: Eyes on timber

Existing laws have different provisions and processes for the felling of trees for forests categorised under national, community, religious, and private headings. The process of felling many kinds of trees is relatively easier in private forests. But for select tree species, one can’t fell them even if they were grown in private forests. The process for felling privately grown trees in villages is complicated even for personal use. There’s a ban on felling of many species of Sal trees, even if they were grown on private forests.

The trend of registering land on private names in the country’s mid-hill section saw a rise after the Ministry of Foresty and Environment introduced a policy last year when it lifted a ban on felling of many species of privately grown Sal trees.

According to members of forest users’ group, even though there was no ban on felling of Sal, Katus and Gurans trees for private use, their trade and transportation was prohibited.

After many individuals and agro companies began to purchase land with forests at various places around the country, the ministry introduced a provision that allowed easy trade, felling and transportation of the trees.

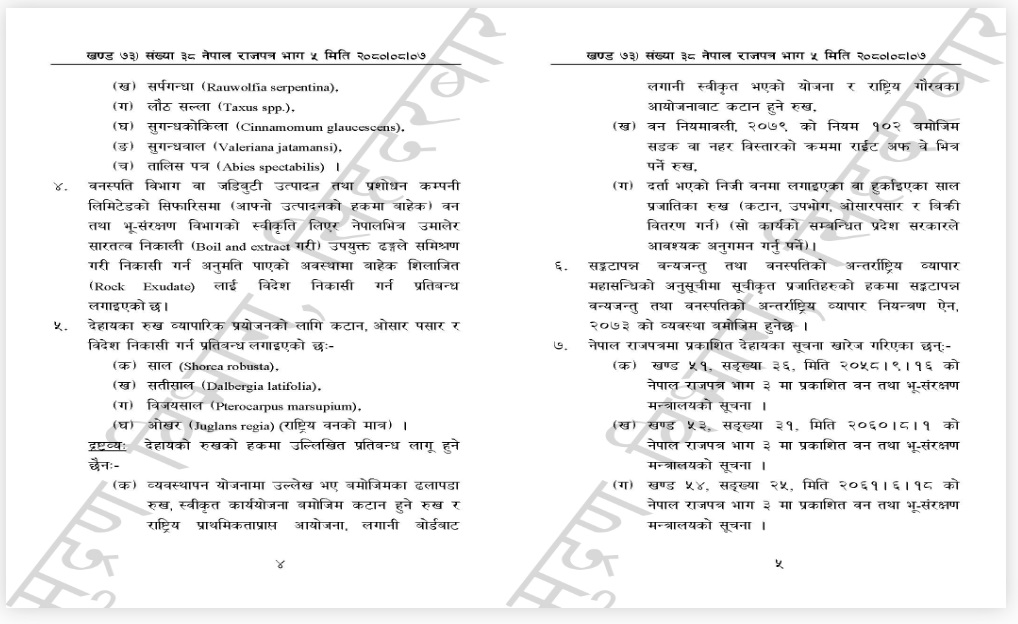

A decision published in the national gazette on November 23, 2023 states that the ban on the felling, use, transportation and trade of Sal trees grown on registered private forests would no longer be effective.

‘We fear there’d be no land left in the village’

Private forest is a jungle grown on an individual’s land. But the government doesn’t treat it as an automatically private forest. Only after it is registered with the local unit with recommendation from Division Forest Office does it get the approval as a private forest.

The District Forest Offices formed before the federalism’s implementation are now under the provincial governments as Division Forest Offices. According to those knowledgeable about the matter, registering private forests tends to be a hassle due to the influence of middlemen.

The government’s decision last year regarding the felling of trees is even more surprising. The government has titled the decision ‘ban on forest production and supply’ and only in its body text has it mentioned that the ban has been lifted.

The decision published in the gazette on November 23, 2023 mentions that there is a ban on forest production, collection, use, trade, transportation and export. On a cursory glance, one can only see the ban in place for the export of herbs and plans. The clause 5 mentions that there’s a ban in place for the felling, transportation and export of Sal, Satisal and Bijaysal trees.

But the text of that clause also mentions conditions on which the ban would not apply. The heading that mentions the ban also mentions that on the felling, use, transportation and trade of Sal species trees grown on registered private forests, the provincial government would monitor it as necessary.

The notice was issued as per clause 77 of Forests Act 2076 BS, which mentions the provision to put a ban on the export of timber. The clause, titled ‘Power to impose restriction’, states, “The Government of Nepal may, by a notification in the Nepal Gazette, impose restriction on the collection, cutting, use, transportation, sale, distribution or export of the prescribed forest products for the purposes of protection of bio-diversity, any species or environment.”

The decision appears to be made by the Cabinet meeting of November , 2023. The clause 15 of the decision, available at the website of the prime minister’s office, states that a ban would be in place on the collection, cutting, use, transportation, trade and export of herbs like Panch Aunle and trees that are important regarding the conservation of biodiversity and species.

At first glance, one understands that the Cabinet made a decision for conservation of biodiversity. The proposal also included a prohibitory clause regarding the lifting of the ban on tree felling but the Cabinet decision and gazette’s notice do not reveal that. The Forest Ministry had highlighted the lifting of the ban on its website.

Jograj Giri, chair of the Association of Family Forest Owners, Nepal, says the government has made a policy decision aimed at benefitting timber traders at a time when people at many places from Ilam to Dadeldhura have been unable to use trees grown on their own land.

Jograj Giri, chair of the Association of Family Forest Owners, Nepal, says the government has made a policy decision aimed at benefitting timber traders at a time when people at many places from Ilam to Dadeldhura have been unable to use trees grown on their own land.

“Many people who own private Sal forests have had to buy timber from elsewhere to build homes,” Giri said. “They can’t use up timber from trees grown on their own land. But now, the government has made a decision to allow the felling of trees by registering such land as private forests. Timber traders around the world are now active in purchasing those lands.”

Madhav Raj Khanal, a teacher from Arghakhanchi’s Shitganga, says that after Khoriya lands began to get sold in speedy manner, many locals tried to register their land as private forests but authorities tend to turn them back saying they have no policy at place at present to register private forests. Technicians at Division Forest Office, however, have been facilitating the registration of such lands in the names of agro businesses and their trade.

Giri adds that while the government is selling timber from community and public forests, it has restricted farmers from using timber from trees grown on their own land and has now introduced a policy favourable to timber traders. “We had been raising voices to lift the ban on felling of trees grown on farmers’ lands,” Giri says. “While the government has prohibited small farmers from felling trees, it has introduced a policy favourable to powerful timber traders.”

Even though the notice the government has published in the national gazette mentions the ban on felling of Sal trees has been lifted, it requires crossing several complex processes to do so. First, one has to register the land as private forest. Then, take permission from Division Forest Officer and then register it at the local unit concerned.

“For those who don’t have political clout and influence, it’s hard to register the land as a private forest,” Giri says. “Rangers tend to turn one back stating at least two third of the land should be covered with trees. But timber traders with political clout tend to get through and get the land registered as private forests.”

According to Environmental Statistics of Nepal 2024, the number of private forests stands at 2458 in Nepal, covering 2360 hectares. But Giri says that the statistics reflect only the registered land while the number is much higher than that.

The government indeed has not authorised family forests, even if it has private ones. If the family forests are not registered, they are not counted as private forests. Giri adds that as many as 20,000 households own private forests.

Secretary at Forest ministry Deepak Kharel says that production from private sector covers two third of the Nepali timber market estimated to be of 35 million cubic metre timber. Once the latest policy is implemented, more timber is set to come from the private forests.

Deputy Mayor Geeta Bhat of Shitganga Municipality says that the recent trend of unchecked land trade risks upending whole settlements. According to her, many traders are taking out loans from banks and cooperatives putting those lands as collateral.

“As the trend has spiralled out of control, we have introduced a policy to discourage it,” she says. “We have begun to ask the reason for purchasing large swathes of land. The ward gives permission only if it receives a satisfactory response. Else, no land would remain in villages that’s not used for blind pursuit of wealth.”

Government claims no ill intention

The decision was taken during then Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s tenure when Dr. Birendra Prasad Mahato was the Forest Minister. Records show that ministry secretary Dr. Deepak Kharal had taken the proposal to the Cabinet. Shiva Kumar Wagle was the director general of Forest and Land Conservation Department.

The Forest Ministry had received endorsement from the Finance Ministry before forwarding the proposal. Records show that then Finance Minister Dr. Prakash Sharan Mahat had given the permission through ministerial decision on September 21, 2023.

The Forest Ministry had received endorsement from the Finance Ministry before forwarding the proposal. Records show that then Finance Minister Dr. Prakash Sharan Mahat had given the permission through ministerial decision on September 21, 2023.

While allowing the permit for Sal timber supply, Minister Mahat had also offered his written suggestion. He had witten that it would be appropriate to allow the felling, transportation and supply of private forest products on the recommendation of the agencies concerned.

Then Forest Minister Mahato said that the decision to allow the felling of Sal trees grown on private land shouldn’t be taken otherwise. “We forwarded the proposal after there was lobbying to allow the felling of trees grown on private property,” Mahato said. “We granted the permission on the condition that the local unit and Division Forest Office would also be involved in it. There’s nothing suspicious about it.”

Then the Cabinet appears to have taken the decision after receiving approval from the Finance Ministry and other agencies concerned under provincial ministries.

Officials at the Forest Ministry also claim that there is no foul play in that decision. The decision was made prioritising consumers’ benefits. “Our motive is to allow the landowner to take benefit from their produce,” Kharal says. “With the decision, we aimed to encourage the private sector to cultivate forests and also to facilitate timber trade. There’s no foul play involved.”

Benefit to traders on the pretext of consumer rights

Traders say that the price of Sal timber in the market is exorbitant now. A good quality Chiran timber is being sold at Rs 5,500-6,000 per square metre. Raw Goliya timber is supplied after paying a tax of Rs. 1200-2200.

About 100 cubic feet of timber can be extracted from a Goliya of an average Sal found in Tarai and Chure range. Exporting the timber from a single Sal tree requires paying at least Rs. 40-50,000 royalty. Hence, a Sal tree costs at least Rs. 70-80,000.

But according to local teachers, people’s representatives and local residents, the Khoriya lands in the mid-hill region are being sold at a very cheap price. Even the most expensive cost Rs. 40-50,000 per ropani and hence, the traders are seeking to reap heavy benefits.

Shiva Kumar Wagle, director general of Department of Forest and Land Conservation, is aware of the trend. He says those with land registration certificates can’t be stopped from selling their land, and expressed suspicion that big traders might take advantage of the decision.

“It would be better if the farmers had sold the timber themselves, without selling their lands. They didn’t understand that they could sell timber after the ban was lifted,” Wagle says. “They didn’t perhaps have the confidence to do so.”

The Schedule 5 of Nepali constitution includes National Forest Policy among the jurisdiction of the federal government. The issues inside the provinces (Schedule 6-19) fall under provincial governments’ jurisdiction while the issues related to forests and wildlife also fall under the common jurisdiction of all three levels of government. There’s a legal provision mandating provincial and local units monitoring all aspects of local forests.

After the country adopted federalism, local and provincial levels shoulder all responsibilities regarding forests, except for some policy decisions. The District Forest Offices have transformed into Division Forest Offices, which are under the provincial governments.

Many issues related to the felling of trees in community forests and timber management of national forests come under provincial ministries; else, the Division Forest Office concludes many issues itself. The local units have the rights regarding registration of community and private forests.

But the federal government has lifted the ban even before formulating basic legal criterias regarding the roles of local level, Division Forest Offices, and provincial forest ministry. “While the general public can’t register private forests, the traders can do it easily colluding with officials,” Giri says. “So who exactly does this policy benefit?”

Wagle says that since the process to grow Sal saplings is different than other plants, there needed to be a strong policy in place from the federal level. According to him, Sal trees can’t be planted, they grow naturally, and take 30-40 years to mature.

“This is why there was a ban on felling Sal trees for long. Now it’s been lifted according to consumer demands and necessity,” he says. “This is now the right of the provincial government. It can monitor and permit the felling of the trees by formulating a working procedure. The federal government has done its share of work by lifting the ban. The ball is now in the provincial government’s court.”

Prabhat Sapkota, spokesperson of Lumbini provincial forest and environment ministry, says that felling of Sal trees would be easier after the provincial government formulates a working procedure. But such a procedure would apply not for those who own only a few trees but for those who register private forests, he says.

“The government has decided to allow the felling of Sal trees on private forests,” he adds. “Once the working procedure is formulated, permission can be granted to fell trees in private forests at once. I don’t think this process would make it easier to fell a few trees.” Sapkota’s views also point to the fact that the decision is not likely to benefit small farmers.

Dr. Rajesh Rai, a professor of forest science, says that only a Sal tree that is over 50 years of age can be used to prepare furniture used at home. But due to the ban, farmers couldn’t use the trees they grew for a long time in their own lands.

And the recent lift in ban, said to be addressed towards fulfilling the farmers’ needs, is also likely to benefit timber traders more. Though local units have many rights regarding forest management, they lack capacity to act on them and the Division Forest Office is holding sway.

According to a farmer who has knowledge about the matter, officials at Division Forest Office have been accused of collusion with timber traders and hence haven’t been able to work for farmers’ rights. It’s certain that the government’s latest decision is also set to benefit traders instead of farmers.

“It’s hard to register private forests, fell trees, and there are other complex processes related to transportation, among others, which have barred small farmers from taking benefit by selling timber,” says Rai, who is affiliated with Tribhuvan University’s Forest Research and Training Centre. “In our society, many policy decisions are made to serve private goals. In such a situation, the chance of the real stakeholders benefitting from those decisions is negligible.”

More Investigative Stories

In Koshi Province, DPRs worth millions for projects never to be built

Many detailed project reports (DPRs) prepared by the Koshi provincial government at the cost of tens of millions are shelved....

Uncooperative cooperatives

A Rs1 billion project aimed at promoting farmers failed due to mismanagement

Comment Here