Investigative Stories

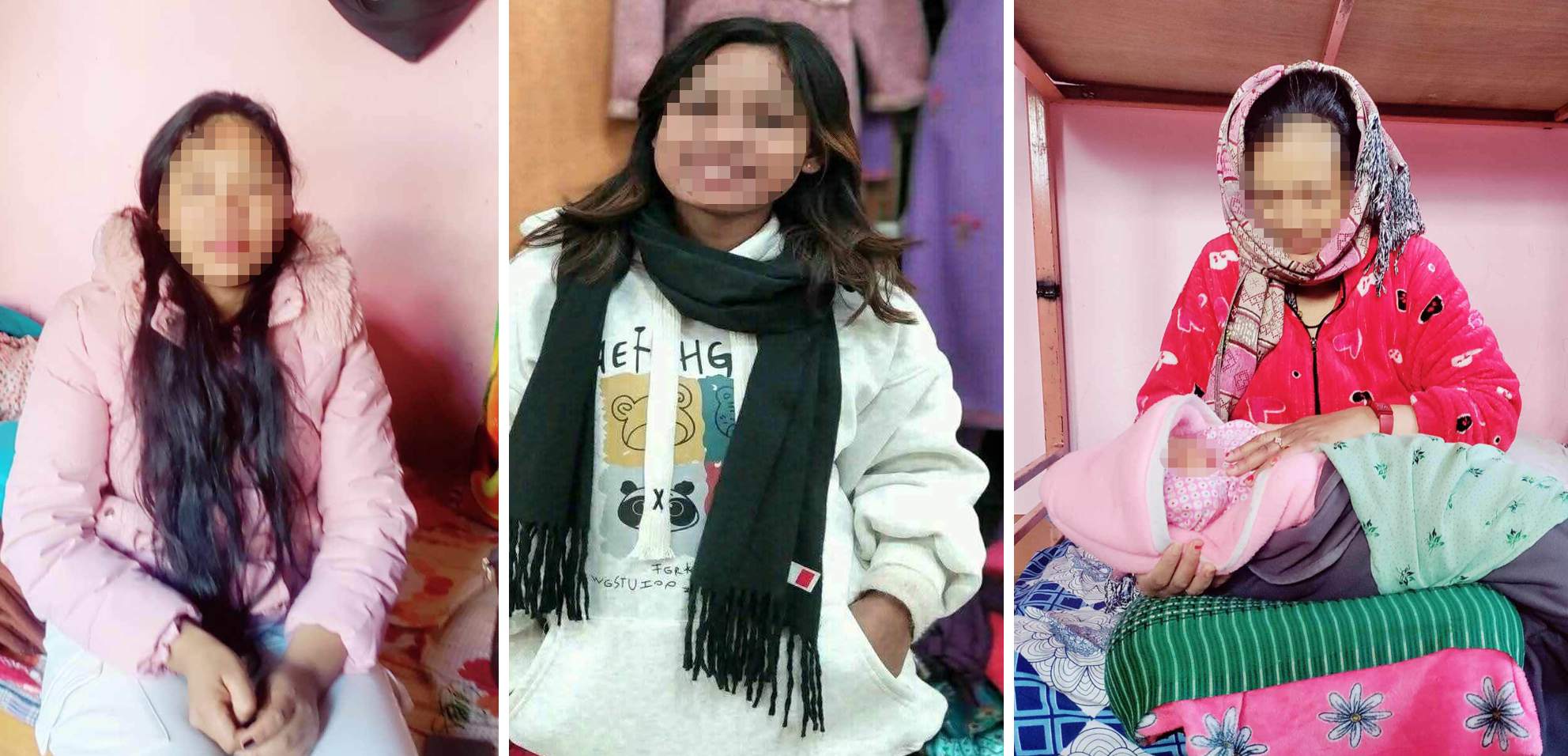

Uma Pakhrin took a loan of Rs15,000 at a monthly interest of 5% and made a passport. On 25 September 2023, with some trepidation and some hope, she travelled to Kuwait from Kathmandu airport via Sri Lanka.

Uma was a domestic worker in a family of four. She was responsible for cooking, washing, and cleaning the house. She spent the first month learning the job, but after that, the employer paid her.

Following this, she took a photo of the cash and sent it to a guy she knew from her village who is now working in Saudi Arabia. Only then did she find out she had been taken to Saudi Arabia, not Kuwait.

Uma married her lover at 18 but life wasn’t easy. Her husband went to Malaysia to improve their economic condition but before long he started ignoring her, let alone sending money back home. She struggled to raise her two daughters with the wages she earned from working part-time.

During that time, an acquaintance told her she would get financial support if she went to a church. She started going to one in Bauddha where she met a ‘guruma’ who advised her to go abroad. The ‘guruama’ gave her a loan at a monthly interest rate of 5% to make a passport and introduced her to a broker, Sirjana Tamang.

Sirjana then introduced Uma to Tika Tamang who assured her about foreign employment, saying: “It doesn't cost a single rupee. You don't have to buy anything except clothes. If you get a good house, you will earn a lot. If you get a bad house, you will be transferred to another one.”

When her employer paid her in Saudi riyals and not Kuwaiti dinar as she confirmed by sending the photo of the cash, she recalled being driven in a taxi for five hours, a couple of days after arriving in Kuwait.

Worried and confused, Uma contacted Tika in Nepal. Tika reassured her that if the work was good, it wouldn’t matter where she lived, and Uma acquiesced.

However, the employer stopped paying her soon after. When she demanded her salary after not receiving it for the third consecutive month, the employer proposed a sexual relationship with her. “He said he would give me a lot of money if I had a relationship with him,” Uma recounts. “I refused. After that, he started to mistreat me.”

When Uma refused to work without being paid, the employer started to harass her. “He would enter my room and try to force himself on me. His wife would beat me,” adds Uma. She phoned Tika about her plight following which she stopped answering Uma’s calls.

While sharing her problems with friends on social media, someone suggested that she contact Yam Bahadur Tamu in Riyadh. She reached out to Yam Bahadur through Facebook Messenger and told him about her situation. He in turn advised her to run away with her passport from Jubail where she was employed to Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia.

But first, Uma had to retrieve her passport, which was with her employer. She found where it was hidden after two days but she couldn’t immediately retrieve it. One evening when the whole family was outside enjoying themselves, she entered the house and took her passport from her mistress’s drawer. After everyone fell asleep, she left the house from the back using a ladder she had found in the storeroom earlier in the day.

“It was already 11:45 pm, I didn’t even have slippers on my feet, I was running aimlessly through the streets of Saudi Arabia,” she recalls. “After running for 15 minutes, I was breathless. Then I just sat down on a dune!’

The taxi she had booked arrived only at 1.45 am. After over four hours at 6 am, it dropped her off near Yam’s restaurant in Riyadh. The restaurant was closed.

Barefoot, dirty clothes, unkempt hair -- passers-by started at her as she sat on the street.

A Nepali young man approached her next and asked, “Are you Nepali, sister?”

“Yes.”

“Did you run away?”

‘No, I came to meet Yam dai.”

“Don’t sit on the street like this. Get in my taxi. You can go after the restaurant opens,” he told her.

She fell asleep in the taxi. By then, the young man had bought her a pair of shoes, socks, and clothes. The same young man took her to Yam’s restaurant.

Yam immediately took her to the Nepal Embassy where she received necessary medical treatment. He then made a public appeal on social media and raised money for her return to Nepal. After 13 months of hardship, Uma finally returned home.

---

Archana Rajbanshi, 23, was working at a carpet factory in Nakkhu in Lalitpur. Her father was in Qatar. In May of 2024, her sister and mother came to Kathmandu from Morang, saying they were going to Kuwait. Rajkumar and Suresh in Morang had introduced Archana’s mother Seema to Naresh, a broker in Kathmandu. Naresh also advised Archana to join her sister and mother.

Of the three, Archana’s visa came first, and just a month later, she, along with six other Nepali women were in Kathmandu airport bound to Kuwait via Abu Dhabi. However, immigration officials stopped them. But shortly after, Naresh came and talked to the staff, and they were allowed to board the plane.

The family of Archana’s employer in Kuwait had 15 members, she had to work all day long. “When my clothes got wet while working, I would go to the roof and sit in the sun, I had no other clothes to change into,” she tells us. The employer didn’t even buy her an extra pair of clothes despite her multiple requests.

Fed up, Archana contacted the broker who had sent her to Kuwait and asked him to return her to Nepal. However, he told her she could only return if she paid Rs200,000. Feeling trapped, Archana decided to run away.

In the morning, when her employer went to the office, she slipped out of the house under the pretext of throwing away the garbage. Once she reached the main road, she didn't know where to go and stood by the roadside. But the employer’s son, who was going to college, saw her and took her to his mother’s office. She was scolded and brought back home.

However, at noon that very day, she tricked her way out of the house again and ran away.

The second time, she ran away through the alleys. After reaching a safe distance from the house, she hailed a taxi. The driver was an Indian citizen and took her to the Nepal Embassy. After reaching the embassy, she stayed in a shelter for a month. Later, she returned to Nepal with a flight ticket provided by the Kuwaiti government.

The ban promoting illegal routes

According to a study by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), a significant number of Nepali women started going to Southeast Asian countries for labour starting in the 1980s. By the 1990s, Nepali women were working as domestic workers and employed in service sectors in Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore. In the 2000s, they started going to the Gulf.

In November 1998, Nepali domestic worker Kani Sherpa died in Kuwait. The news broke that she had died by suicide after being raped by her employer.

“The cause of her death is still a mystery,” says Manju Gurung, former president of Pourakhi, an organisation leading the rescue and rehabilitation of women migrants. “Although we were told that she died by suicide after being exploited by her employer, there is no official record about what exactly happened.”

Immediately after the incident, for the first time, the government banned Nepali women from going to the Gulf as domestic workers.

On 27 October 2024, Amritsar Social Organisation rescued nine women from Kuwait and sheltered them. Just two days before on 25 October, the same organisation had rescued seven women deported from Kuwait. The organisation’s president, Muna Gautam, says that they rescue at least one woman every day from Oman and Kuwait.

Most of these women are single, divorced, and victims of domestic violence, and brokers often use their vulnerability and poor economic situation to trap the them, adds Gautam.

Brokers bring women from villages and rent flats in places like Jorpati, Lagankhel, Tokha, Nepaltar, and Bus Park in Kathmandu, adds Gautam: “They send them abroad in groups of 15 to 25 at a time, and therein begins their exploitation by brokers. If the government had sent them legally, they would not have been subjected to the violence and exploitation they are facing now.”

According to Bhavesh Rimal, spokesperson for the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau of the Nepal Police, brokers are still taking Nepali women to the Gulf via India, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka regardless of the ban. This is also despite official claims of stringent measures in place at the airport. Brokers are known to bribe officials at immigration to allow migrants to board the plane even if they lack documentation or with suspicious cases where it is often clear they are being trafficked.

However, the added restrictions at the airport have meant that brokers started sending them via Delhi. But when India also started tightening the restrictions at the request of Nepal, brokers resorted to sending them via other cities and countries including Banaras, Sri Lanka, China, and even Africa.

But according to DB Tamang, former General Secretary of the Home Based Worker Concerned Society Nepal, the Indian government acts at its convenience. When it is strict in Delhi, the Varanasi airport is relaxed. When it tightens restrictions in Varanasi, Bangalore becomes lenient, he laments.

A parliamentary report on 17 March 2017 based on a study conducted by the Labour Committee in the Gulf states that, ‘60% of Nepali women reach the Gulf countries through the collusion of employees of Tribhuvan International Airport, airline companies, and brokers.’ The remaining 40% get there via countries including India, Sri Lanka, China, and even African nations, the report adds.

Added risk of illegal channels

By banning women from going to Gulf countries, the government has essentially increased their vulnerability. Women continue to migrate for livelihood but now they have to use illegal routes and consequently are at greater risk. These women are undocumented and hence not in the government records, making it much harder to rescue them if they find themselves in any trouble at destination countries.

Former president of Pourakhi Nepal, Manju Gurung, says, “For one thing, most of those who go illegally have fake documents. On the other hand, they are exploited by brokers while traveling through various countries covertly.”

Giriraj Acharya, labour attaché at the Nepal Embassy in Kuwait, says that it is not easy to return women who have fled their jobs and reached the Nepal Embassy. “If the employer has filed a police complaint, it is difficult to return them until the case is resolved. Regardless, we fight a legal battle on their behalf.”

The fact that the ban has not stopped Nepali women from going to Gulf countries is evident from the data of the Nepal embassies in the respective countries. According to Giri Prasad Acharya, 40,000 Nepali women are working as domestic workers in Kuwait alone.

Similarly, there are 10,000 Nepali women working as domestic workers in Oman, according to Govinda Prasad Acharya, labour attaché at Oman. Another 5,000 are in the UAE. Jamuna Kafle, labour attaché at the Nepal Embassy in Bahrain, says there are 3,083 Nepali women working over there, 303 of them are domestic help.

Qatar and Malaysia don’t have as many Nepali women working as house help but the officials have had to rescue and return a few individuals every year. Elsewhere, Devendra Karki, labour counsellor at the Nepal Embassy in Saudi Arabia, says that the number of Nepali female domestic workers cannot be confirmed but the embassy rescues and sends back an average of 25 women a year.

Four decades of government incompetency

A study by the ILO in 2015 titled ‘No Easy Exit: Migration Bans Affecting Women from Nepal’ has also noted the government’s changing policies when it comes to the migration of female workers, adding to the plight and confusion of women going abroad for work.

Until 1998, Nepali women required the permission of their male guardians to go abroad. From 1998 to 2003, Nepali women were banned from going to Gulf countries as workers. From 2003 to 2010, this ban was partially lifted. That is, women who had gone to Gulf countries and returned to Nepal on vacation had to obtain permission from the government if they had to go back.

In May 2003, women were required to obtain permission from the local level and their families if they had to go abroad. In May 2005, women were banned from going to the Gulf and Malaysia. In 2009, Nepali women workers were banned from going to Lebanon.

In December 2010, the ban on Nepali women going to Gulf countries was lifted with conditions per which it was mandatory to undergo training, obtain permission from the embassy, maintain regular contact between women’s families and the embassy, and guarantee safety from employers.

During the period when this arrangement was in effect until August 2012, Nepali women also went to work in the service, industry, and construction sectors in the Gulf countries. However, the Cabinet meeting on 9 August 2015 added a condition that Nepali women workers going to the Gulf countries must be 30 or above.

Although the name of the banned countries were not mentioned in the press release issued by the Foreign Employment Board on 3 September 2012, they later stated that the ban was imposed on Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar.

From April 2014, the government stopped granting approvals for domestic workers. In 2015, according to the report of a five-member study committee formed by the Ministry of Labour, the government introduced guidelines on sending domestic workers for foreign employment wherein the age limit for women was stipulated as over 24 years. This age limit was set for Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE, Oman, Bahrain, Lebanon, and Malaysia.

After widespread criticism that the ban put female workers at greater risk, the International Relations and Labour Committee of the Legislative Assembly visited the Gulf and Malaysia. After the visit, the committee’s meeting held on 13 April 2017 directed the government to completely ban Nepali women from traveling to the Gulf and Malaysia to work as domestic workers.

After the ban, Nepali women who had previously travelled to the Gulf and Malaysia to work as domestic workers could not come back even on vacation fearing they won’t be allowed to go back to their jobs.

After many complaints, on 6 September 2019, the government made arrangements to reissue work permits to women who had legally travelled before the ban. However, for that, women had to provide a permit from their employer and confirmation that they had been called back to work.

In February 2020, the Industry and Commerce and Labour and Consumer Affairs Committees again visited the Gulf countries to access the situation. The committee meeting held after the visit again directed the government in September to completely ban Nepali women from going to the Gulf and Malaysia as domestic workers. However, arrangements were made for women who had already obtained work permits to be re-granted work permits based on self-declaration.

The Constitution of Nepal and the Foreign Employment Act 2007 prohibit restrictions on employment based on gender. However, the government has been issuing policies and regulations time and again restricting women’s rights to employment. Various studies have shown that such restrictions have put female workers at a higher risk, exposing them to trafficking, increased bribery and corruption at the airport as well as the higher overall cost of women migrants.

In another instance, despite the government banning Nepali women from traveling to Lebanon in 2010, the Lebanese government issued 3,895 work permits for Nepali domestic workers. This is a clear proof that the government ban hasn’t been effective, states an ILO study. The report also notes that many women took illegal routes via India and Bangladesh following the ban, rendering the restrictions useless but rather exploitative.

The report also points out that the government flip-flopping on the policy has promoted irregularities at Kathmandu airport as the ‘setting fees’ of airport officials have increased.

Labour migration researcher Saru Joshi says that the government banned domestic work without sufficient study and research. Countries other than Nepal are also sending their women as domestic workers in the Gulf but they equip them with adequate training and basic knowledge of the language and culture before departure.

“At least they should be trained in operating household appliances such as washing machines, microwave ovens, and in taking care of children, and they should be able to speak the local language,” says Kishore Pradhan, chair of the Home Based Worker Concerned Society Nepal.

But Nepal has gone done the opposite by banning migration instead of making its workers skilled and competitive. Says Bijaya Shrestha of the Returnee Women Migrant Workers’ Group: “There are problems in every sector. However, bans are never a long-term solution.”

She adds that the government should ensure employment opportunities within the country first and then fully ban Nepalis from going to restricted countries. Otherwise, the ban will only benefit the brokers and put women at risk.

A way ahead: zero cost Jordan

Seven years ago, Nepal and Jordan signed an agreement per which women between 24-35 (up to 40 if they have previous experience working abroad) are sent to Jordan as domestic help. The applicants have to go through a medical examination, following which they are given one-month residential training as well as basics of the local language.

The visa is valid for two years but the employer can extend it if they wish. The salary is between $300-$350 a month while food, accommodation, and other medical facilities are provided by the employer.

Advocate and labour migration expert Som Luintel accuses the government of taking an easy way out by imposing the ban rather than solving the real problems that migrating women face. “Not that it is stopping them from going anyway,” he says, adding that either the government should create employment opportunities within the country or send female workers to countries with bilateral agreements.

Experts say that most of the women migrating for domestic work are from impoverished backgrounds, isolated, and lack education and that the ban has further victimised them.

Mukunda Prasad Niraula, secretary of the Ministry of Labour, Employment, and Social Security, says that preparations are underway to send Nepali women to the UAE as domestic workers with the consent of the labour committee.

“A level-one agreement has also been reached with the UAE government. We are awaiting approval from the Foreign Ministry. If this is successful, we propose it to other labour countries as well,” he adds.

More Investigative Stories

In Koshi Province, DPRs worth millions for projects never to be built

Many detailed project reports (DPRs) prepared by the Koshi provincial government at the cost of tens of millions are shelved....

Uncooperative cooperatives

A Rs1 billion project aimed at promoting farmers failed due to mismanagement

Comment Here